New research shows the Renewable Fuel Standard and its implementation are fueling an environmental disaster that is destroying monarch butterfly habitat and forage, draining western aquifers, accelerating climate change and numerous other effects. The new research, prepared by the University of California-Davis, Kansas State University, and University of Wisconsin, provides the most detailed and comprehensive assessment to date of the direct connection between U.S. biofuels policy and specific economic and field-level environmental changes following passage of the Renewable Fuel Standard 10 years ago.

Read on to learn more about the problem and what is at stake, or view the quick take of the late-breaking research.

Worse than we thought

More than a decade ago, the federal government began requiring that ethanol and other plant-based fuels be blended into our fuel supply. The subsequent intensification and expansion of industrial-scale agricultural production here and around the world has had a huge impact on the environment.

The true scale of that impact has become clearer over time, and newly completed research has eliminated any remaining doubt – America’s biofuel mandate has made our environment worse, rather than better, putting at risk our health and the viability of many wildlife species, while adding billions of dollars in costs to consumers and taxpayers.

Hundreds of scientific studies over the last 10 years have documented the negative effects of growing crops like corn and soybeans and turning them into massive quantities of fuel. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency compiled the findings of many of those studies into an authoritative report to Congress last year. The report’s conclusions were sobering, and new research since the report have only added to the concerning tally:

Citing independent university research as well as surveys conducted by the U.S. Department of Agriculture, the EPA report confirmed that commercial crop planting had expanded following the mandate – to the tune of between 4 million and 7.8 million acres nationwide. A recently updated analysis from the University of Wisconsin shows that conversion has continued in the years following the timeframe considered in the EPA report, bringing the total to more than 10 million acres.

For scale, that is an area twice the size of Massachusetts that has been newly plowed for crop production, much of it for fuel crops like corn and soybeans. This expansion countered a long-term trend of declining farmland in America as the country has become more urbanized and agricultural production has become more efficient and highly concentrated to fewer, larger farms. So while overall crop acreage today is roughly the same as it was back in 2007, cropland lost to urbanization in certain parts of the country has been offset by new acres broken out in other places.

The University of Wisconsin has used satellite images to show exactly where this destruction is occurring, and its latest research has shown that it has continued even as biofuel production has plateaued, showing the dynamic nature of land use, and how uncultivated habitats remain at risk of conversion.

However, the EPA, as well as the ethanol industry, has repeatedly stated that there has been no link showing that the biofuel mandate was responsible for this expansion, as opposed to other factors such as increased demand for American agricultural products overseas. The new findings explicitly make that link to show just how much the policy has driven land use change by providing the incentive to plant crops in new areas, and the associated environmental impacts.

The research has found that higher crop prices due to biofuel demand led farmers to plant on 1.6 million new acres of land, or about 15 percent of the larger expansion during the years 2009 to 2016. These higher crop prices also caused farmers to keep land in production that otherwise most likely would have gone into a conservation program or left fallow as pasture – land that was marginal for optimum farming and thus not profitable under normal crop price scenarios – to the tune of maintaining an additional 1.2 million acres of crop production.

Adding up the crop expansion and the foregone land retirement, and the biofuel mandate was responsible for 2.8 million acres of additional cropland in production, or 43 percent of the overall expansion observed. To put it another way, the cropland expansion during those years was 73 percent larger than it would have been without the policy. This direct link and analysis has never been made before.

While cropland expansion was concentrated in certain hot spots, even in areas with less agricultural production, communities all around the country have seen native prairie, wetlands, forests, and other wildlife habitat destroyed to make way for industrial crops. Habitat loss is one of the main threats to America’s wildlife populations, and the changes seen in the wake of the biofuel boom have only made things worse.

Wildlife in Peril

Consider the monarch butterfly. This iconic species spends its winters in Mexico before migrating through successive generations all the way up to Canada for the summer, and then back down to Mexico. Despite a significant increase from 2018 to 2019 of monarchs on the winter counts, population numbers have been on a steady decline, reduced by about 80 percent over the last 20 years, and the species is currently being considered for listing under the Endangered Species Act.

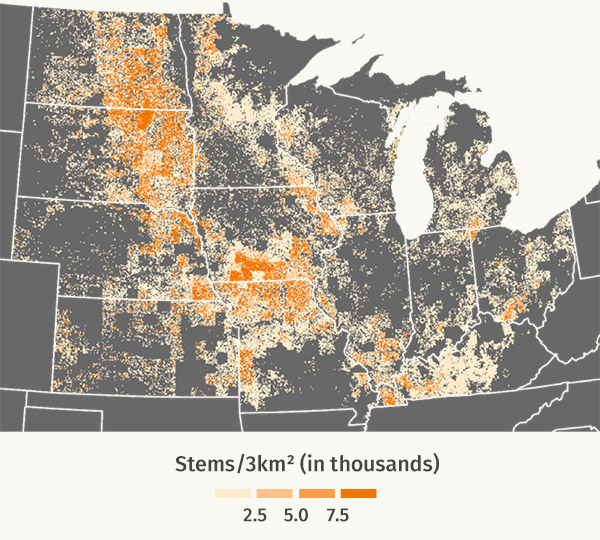

Milkweed stems lost

The latest evidence shows how demand for biofuels has contributed to this decline. The University of Wisconsin estimates that conversion of land into crop production in the Upper Midwest between 2008 and 2016 resulted in the destruction of 17 percent of the region’s milkweed plants. Monarch larvae rely almost exclusively on milkweed plants, making them essential for the species’ survival.

Similarly, the UW researchers found that conversion of land to row crops in the Northern Plains, which contains the single most important breeding grounds for waterfowl in the United States, was skewed to the lands that were most likely to support waterfowl breeding pairs. In all, habitat used by about 276,000 adult birds was converted from grassland or wetland habitat into crop production. All told, one-third of all grassland birds are at risk, largely because of loss of habitat, particularly due to agricultural conversion.

The ducks, geese, cranes, and other birds born and raised in these areas in the spring and summer travel to all corners of the country during the rest of the year, meaning destruction of these breeding grounds ripples out to ecosystems across North America, impacting the birders, hunters, and others who interact with them.

Putting our Environment in Jeopardy

Not only does land conversion eliminate benefits like wildlife habitat, but it also releases a tremendous amount of carbon that had been stored over decades in the soil and the plant material.

This massive land conversion emitted as much climate pollution as the 30 million additional cars on the road during the height of agricultural expansion – more than 10 percent of the U.S. fleet. The annual emissions from the RFS-induced land conversion were equivalent to 5.8 million cars on the road, or 7 coal-fired power plants.

Biofuel production has also helped spur the flow of carbon pollution into the atmosphere globally as well. Large portions of the world’s tropical rainforest have been felled in South America, Indonesia, and Malaysia to make way for palm and soy plantations to produce vegetable oil. Biodiesel made from this oil is part of the growing biofuel mandate here in the United States.

Taken together, land conversion to produce biofuel crops has helped hasten the dire impacts of climate change, making our biofuel mandate part of the problem rather than a solution.

In addition to fouling our land and air, biofuels also have dirtied our water. Taking millions of acres of un-farmed land and plowing it up for industrial crop production sends massive amounts of pollution downstream, contaminating drinking water wells and reservoirs, swimming holes and beaches, and the coastlines that support recreation, tourism, and the seafood industry.

Soil washes off of tilled and erosion-prone farm fields in rain storms. That soil carries with it the pesticides that were sprayed on the crops as well as the fertilizer that feeds them. Fertilizer provides nutrients the plants need to grow- namely nitrogen and phosphorous. When these nutrients occur in water bodies at high levels, they spur the growth of algae, sometimes at extreme rates. Thus, while fertilizer may be good for crops, when they wash off, they become nutrient pollution.

The Human Cost

This pollution hurts people as well as aquatic ecosystems. Algae at extreme levels clogs fish gills and lowers visibility for other organisms, pushing them to migrate away if possible. When it dies, its decomposition sucks up the oxygen in the water, suffocating other creatures and resulting in “dead zones” like the one found in the Gulf of Mexico each summer. And some types of algae produce a toxin that kills aquatic life and is also harmful or lethal to other animals and people who come in contact with the water.

A large bloom of toxic algae caused Toledo, OH to shut down its drinking water supply for three days in 2014 because it was unsafe. Every summer there are numerous beach closings around the country because of algal blooms. The fishing and tourism industries are hugely impacted.

Finally, nutrient pollution – particularly of nitrogen – is also directly dangerous to humans. Water utilities spend billions of dollars a year removing these nutrients before they reach your household, and that cost continues to climb as ever more fertilizer is applied to fields. Rural homes that draw on well water lack that line of defense, and an increasing number of them suffer from nitrate levels deemed unsafe. Nitrate pollution can result in a number of ailments, and can even be fatal to infants.

If all of these serious environmental impacts have been known, and if the EPA itself has documented them, why hasn’t the policy changed?

Why Hasn’t the Policy Changed?

Politics

Part of it is politics, plain and simple, with a vested industry and strong political allies fighting to preserve the status quo. Another factor, however, is the fact that most of the scientific studies to date have consisted of modeling hypothetical scenarios, or have observed trends in the environment that have not been linked specifically to one policy or change on the landscape.

That is no longer the case. As part of its research on environmental impacts, a consortium of researchers from the University of Wisconsin-Madison, University of California-Davis, and Kansas State University has just issued stark new findings of the link between the Renewable Fuel Standard (RFS), as the biofuel mandate is officially called, and the land conversion and pollution that have been observed since the program was created in 2007.

New Demand has Raised Prices

Through rigorous economic analysis, they found that new demand for corn and soybeans to use for fuel has raised the prices farmers receive for those crops – as well as other crops like wheat and cotton that compete for the same farmland – by as much as a third.

Once the RFS policy helped make crops more profitable, that in turn made crop land more valuable and, therefore, more desirable. The research draws the clear link between crop demand driven by the biofuel mandate and the resulting cropland expansion and production intensification. Over 40 percent of this expansion, as well as the drastic and widespread environmental consequences that followed can now be traced directly to this federal policy.

Degradation of wildlife habitat, endangered and beloved species, water quality, and even human health – any way you slice it, the RFS has been a disaster for the environment.

What Needs to Happen

The evidence is in, and it could not be more clear that the time has come for Congress and the Administration to take action to rein in the biofuel mandate to prevent further damage to our shared natural resources. Concrete steps can, and must, be taken to ensure that biofuels are providing a responsible transition to clean, sustainable transportation. Such measures were included in legislation called the GREENER Fuels Act, introduced last year in both the U.S. House and Senate.

These measures include:

Reducing the size of the biofuel mandate so that it does not overly burden land and water resources

Lowering, over time, the share of fuels made from crops like corn and soybeans that have the largest environmental footprint

Putting in place the right blueprint for alternative fuel sources to succeed and grow

Enforcing the existing land protections that have been roundly ignored

With the need to address the climate crisis only growing more urgent, the policies devised to do so must be responsible and not drive unintended consequences like those that have been documented following the RFS. Similarly, policy makers must be willing to adapt in the face of hard scientific evidence that a policy is not living up to its goals.